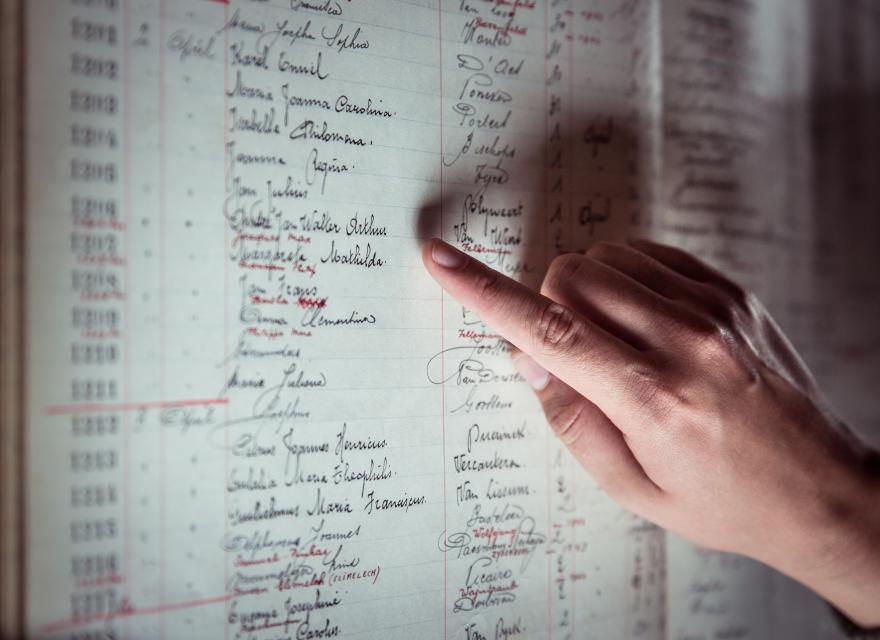

Historical insight through many hands

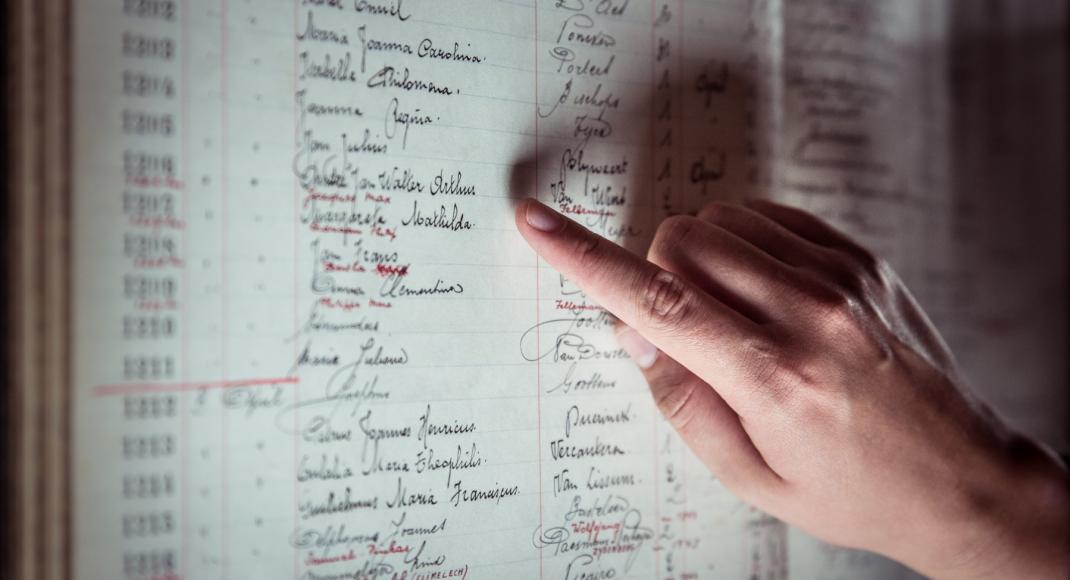

In record timing of ten months, no fewer than 720 volunteers plowed through tens of thousands of scans of the Antwerp City Archives. They noted names, occupations, dates of death and causes of death of the Antwerp residents who died between 1820 and 1946. In this way they have unlocked a unique archive that UGent in collaboration with University of Antwerp, Antwerp City Archives and Histories vzw is being studied. The project is called S.O.S. Antwerpen, Social Inequality in Mortality. Sarah Heynssens, scientific collaborator and volunteer coordinator and professor Isabelle Devos, affiliated with the History Department and the Quetelet Center for Quantitative Historical Research of Ghent University, emphasize in a conversation the importance of the work of their volunteers and advocate for historical citizen science projects.

Gold mine for research

Between 1820 and 1946, nearly half a million people died in Antwerp. The Antwerp City Archives keeps a register in which the date of death, age, cause of death, profession, marital status and all kinds of personal data are stated for each deceased during that period. S.O.S. Antwerp wanted to transcribe this register together with careful volunteers, that work is now almost finished. After the introduction of the data, the analysis by scientific teams from different disciplines, the publications and the insights follow.

What makes the register of causes of death of the Antwerp City Archives so unique?

Professor Isabelle Devos: Since 1851, every Belgian city or municipality has to keep a register of causes of death. These data were destroyed for privacy reasons after overview statements were made. For one reason or another, perhaps because it was realized that this was unique data, the handwritten register in Antwerp was never destroyed. Moreover, a register was started in Antwerp in 1820 and the data continues uninterrupted until 1946. For example, we have data on both World Wars, which is very exceptional. A cause of death registry of a major city that has been preserved over such a long period of time is truly a gold mine for scientific research.

A cause of death registry of a major city that has been preserved over such a long period of time is truly a gold mine for scientific research.

Social inequality

With the data from the register in hand, what exactly do you, as historians, want to examine?

Professor Isabelle Devos: In essence, we at S.O.S. Antwerp want to support and stimulate scientific research into disease and mortality in Flanders and to look in a very concrete way for the historical roots of social inequality in health according to occupation, origin, age and gender. In this way, we hope to gain a broader historical understanding of advances in public health and living standards over the past two centuries. If we make that concrete, it means, for example, that we learn more about cholera, tuberculosis, the Spanish flu, cancer or other causes of death in the 19th and 20th centuries. Or we can detect what people succumbed to in Antwerp during the First and Second World Wars, whether women in the past also lived longer than men, how many infant deaths and stillbirths the city had and which occupations were the worst for health. The average life expectancy in the middle of the nineteenth century was 40 years, now it is 80 years. We want to find out which groups were most vulnerable, in which groups cancer as a disease of old age manifested itself first? Were these the best informed groups in terms of disease prevention, for example?

Corona in the 19th century

That is why the digital access to the register is also interesting for other scientific disciplines?

Professor Isabelle Devos: Indeed, the great thing about our project is that so many follow-up studies are possible. I myself am a historian and demographer, but there are also historians with other specialties and other scientists (such as epidemiologists, geneticists, economists) who will interpret the data. For example, the fact that the registers also include the two World Wars, gives us an insight into the civilian victims of the violence of war. We also compare the data with the headlines of the time. The Antwerp Names Project, which makes an inventory of the data of war victims who lived or died in Antwerp during the Second World War, will be able to use our database. The EPIBEL research project has recently started, comparing 5 epidemics (medieval plague, early modern dysentery, 19th-century cholera, the Spanish flu, and corona): who were the victims, what policies were pursued, and how did these epidemics affect inequality? The historical study of these epidemics can give us insight into today's approach. S.O.S. Antwerp will be able to provide unique data for this. According to virologist Marc Van Ranst, there could have been a corona epidemic as early as the 19th century, from 1889 to 1892, of course we want to check that!

The 'VeleHanden' (Many Hands) input platform ran smoothly, but the key to success is without a doubt patience and quick answers to questions. For many, it became an addiction to enter data.

Many Hands, much patience

It was unexpected that you were able to tackle the register in record time with the help of no fewer than 720 volunteers?

Sarah Heynssens: In a way, yes. During the corona pandemic, volunteers had more time to enter data, they were given a nice puzzle job and could enter at the time of their choice. The threshold for becoming a volunteer was very low, a PC and an internet connection were sufficient to get to work via the 'VeleHanden' (Many Hands) online crowdsourcing platform. We also made sure we were quick on the ball. The helpdesk, which had to process many more questions than initially estimated, was available 24 hours a day, 7/7 and very clear, simple instruction videos were also made. The VeleHanden input platform ran smoothly, but the key to success is without a doubt patience and quick answers to questions. For many, it became an addiction to enter data.

Professor Isabelle Devos: A historical citizen science project is in fact exceptional in Flanders. That's a shame, because many people are busy with history in their spare time. They are interested in genealogy or are involved in a local history circle. If you had told me five years ago that I would be working on a science history project with over 700 volunteers, I wouldn't have believed you. I was convinced that you had to have a history degree to collect historical data. Our project has shown that it is possible. Each entry in the database is entered by two people and then additionally checked, many hours go into the guidance and control, but the result is fantastic. The potential of such a motivated group is enormous, they often input better and more accurately than our students.

Follow-up studies

That is also the reason why you will again engage volunteers in a follow-up process?

Sarah Heynssens: We now want to link the data to the death certificates that also contain the address of the deceased. Later on, in collaboration with the Center for Urban History of the University of Antwerp, we also want to link these to land registry maps. In this way we also hope to map social inequality in mortality. An occupation does not say everything about living conditions, but the location and the cadastral income of the home do give an indication of prosperity. Working groups have now been set up to take on these follow-up tasks. Meanwhile, similar projects are underway in ten other foreign ports. We have united in a network, appropriately named SHiP (Study of History of Health in Port Cities). In the coming years we will compare our data. Because we want to compare the causes of death in those different cities, we must all use the same classification of causes of death. Therefore, we will code and classify the causes of death in all these cities in the same way. We will also standardize the professions, and the volunteers will help with that again.

Professor Isabelle Devos: In the future, we also want to investigate whether there is a relationship between religion and the cause of death. The register also contains the cemetery and the name of the undertaker, which we can link to the religious background. For example, we know from historical research from abroad that Jews usually lived longer than Catholics and Protestants. How did that happen? Does it have to do with different dietary habits and food preparation? Or is it related to a more hygienic lifestyle? Or are there hereditary factors? The cause of death can give us a better understanding of that.

Odd man out

The cause of death register seems to be an inexhaustible source of information. What historical topics have surfaced that require further investigation?

Professor Isabelle Devos: Antwerp became the largest city in Belgium in the 19th century and was a very dynamic port. Millions of Europeans left for America via Antwerp. You would expect that living conditions there, especially in times of epidemics and infectious diseases, would be worse because there was so much mobility. But if you look at life expectancy, Antwerp was a fairly healthy city at the time, much healthier than Brussels, for example. If you didn't want to live somewhere in the nineteenth century, it was in Brussels. But why was that? We suspect that in Antwerp the so-called healthy migrant effect played a role (healthy people migrate, not the sick) while in Brussels it had to do with the poor working conditions (small, poorly ventilated workshops). Again, the information about the cause of death (linked to age, occupation, and address) may be key to confirming or disproving our hypotheses.

Can we consult the digital register ourselves?

Sarah Heynssens: After the project has ended, the data entered will be available to the general public and, of course, to all scientists in the Felix Archive, where everyone can search for the cause of death of his or her Antwerp ancestors. In our newsletter and on our website S.O.S. Antwerp you can also read all about our interim results. This online communication is an essential pillar for us. 99% of the people who enter data for us prefer to work alone on the project and the fact that they remain anonymous is an added value. That makes us rather the odd man out within the classical citizen science projects.

Professor Isabelle Devos: A wonderful odd man out.

Interview and text: Hilde Devoghel (Tales and Talks)

Pictures: An Van Gijsegem