The power of citizen science: how mini-gardens are socially binding

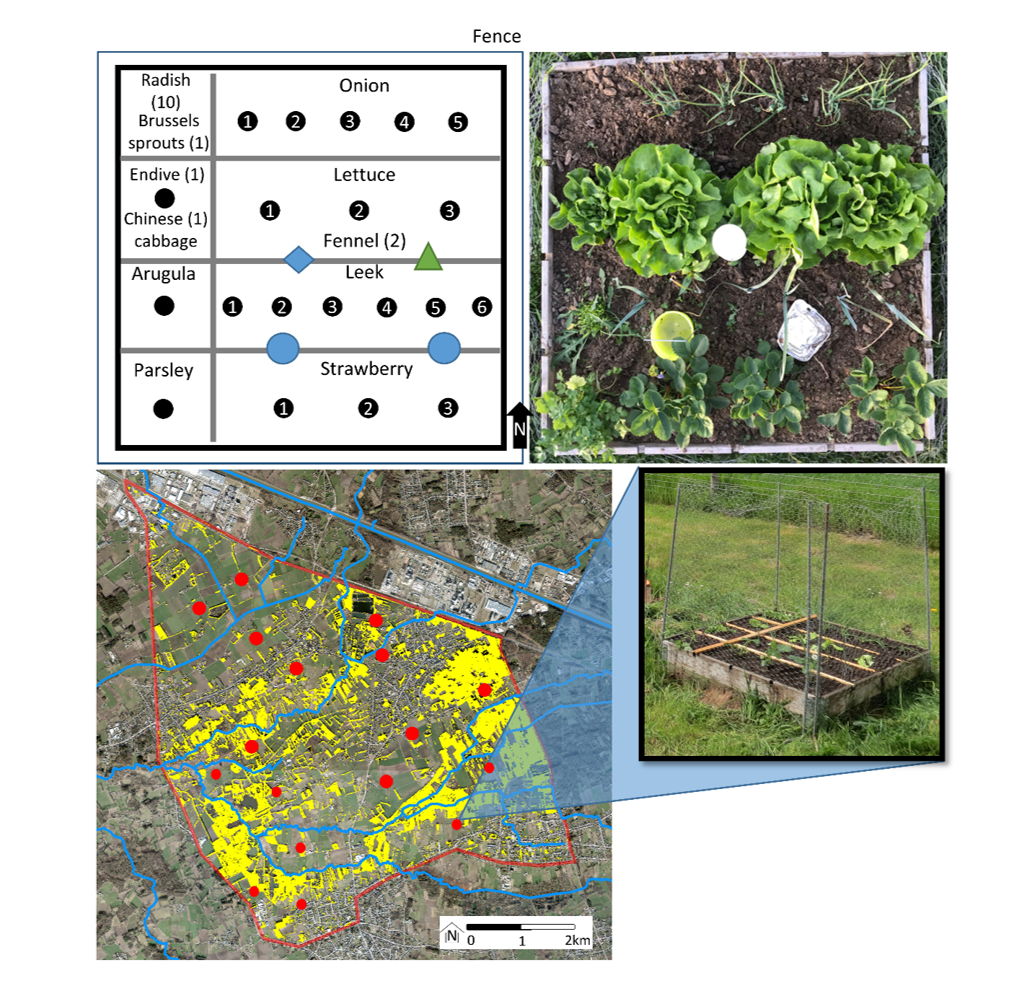

'Citizen science has an enormously connecting character, it is so much more than just collecting data', says Frederik Gerits, scientific researcher affiliated with ILVO (Institute for Agricultural, Fisheries and Food Research). Frederik, who obtained his doctorate at Ghent University and ILVO, studied the harvest of square meter gardens, i.e. identical gardens of 1 square meter in which crops such as leek, onion, fennel, parsley, radish and strawberry were grown. He examined the influence of the microclimate, the landscape and insects on the vegetation in those gardens. The mini-gardens could count on the attention and commitment of gardeners, with or without experience, who supported the research as citizen scientists. Frederik not only looked for ways to increase both the ecosystem and the vegetation in these vegetable gardens, he also looked at how he could stimulate the learning outcome and the learning process of the volunteers through collaborative citizen science. In an enlightening conversation, he explains the insights he came to.

Open-air labs

Vegetable gardens of barely 1 square meter were particularly valuable research measuring points for you?

Frederik Gerits: The gardens were equipped with sensors and insect traps. We wanted to map out the natural enemies, the pollinators, in short the insect community. For example, we found that there was a high activity of useful insects near open farmlands. The more buildings there were in the area, the less activity we registered. We also saw differences in soil moisture and temperature. Wooded edges in the landscape, for example, clearly had a wind-inhibiting and buffering effect. On an ecological level, we were therefore able to formulate conclusions in terms of microclimate and biodiversity via the measurement points in our gardens. Ultimately, of course, as scientists we want to know how we can improve and promote pollination, how we can control pests and diseases and how we can improve the soil and water quality of our fields and our vegetable gardens; so that agro-biodiversity is a win-win situation for both farmers and gardeners.

If you want to go further than just collecting data with a citizen science project, there are a number of rules of thumb. Communication and informal interaction are essential.

Learning process and learning outcome

It is striking that thanks to the volunteers you have come to an extremely high-quality dataset. How did you go about this?

Frederik Gerits: The volunteers took care of their mini garden by watering, weeding, observing and recording dates on a weekly basis. As a researcher, I personally visited them every two weeks for a general inspection, the emptying of the insect traps, the climate sensors and I also held an informal chat. That chat was supplemented with written communication, every Wednesday there was a new newsletter with explanations and facts and the Facebook group also became a lively community of gardeners and scientists.

To what extent was this exchange of both formal and informal communication important to your research?

Frederik Gerits: This exchange was especially crucial for the second part of my research, in which I wanted to investigate to what extent the knowledge acquired by the citizen scientists had also influenced their behaviour, in other words whether there had been transformative learning. To what extent had there been prior knowledge, what facilitated their learning outcome and did they effectively work with new instrumental knowledge afterwards? To answer those questions, I worked with a post-project questionnaire that collected quantitative and qualitative data.

Citizen science can create strong connections. Everyone is committed to the landscape and with a citizen science project you can avoid unnecessary polarization between agriculture and nature and you can focus on constructive dialogue.

Dialogue

Could you explain the process of transformative learning?

Frederik Gerits: The answers to the survey gave us a number of important insights. If you want to go further than just collecting data with a citizen science project, there are a number of rules of thumb. Communication and informal interaction are essential. You get the best results if you combine written communication with active experiments. In this way, citizens receive knowledge at quiet moments and can immediately put it into practice during their measurements. Using the prior knowledge of your respondents, stimulate and show the enthusiasm and dedication of both the team of citizen scientists and the scientists, which increases motivation and facilitates the learning process.

Enthusiasm and dedication are key elements to focus on behavioral change with a citizen science project?

Frederik Gerits: For compelling and transformative projects, so-called immersive citizen science, to succeed, they are indispensable. The seed that you can plant thanks to such a project continues to grow. In that sense, citizen science also has the power to build a social network, to create a coherent sense of community. For example, I can say that apart from the project and the gardens, our community has also led to social gatherings, bike rides and walks. Citizen science can create strong connections. Everyone is committed to the landscape and with a citizen science project you can avoid unnecessary polarization between agriculture and nature and you can focus on constructive dialogue. That potential to break through barriers is present in so many citizen science projects, we just need to focus more on it.

Interview and text: Hilde Devoghel (Tales and Talks)